Two thousand, four hundred and sixteen years after Socrates’ execution for “corrupting the youth” with free thinking, many countries are still not safe places for intellectuals who question the status quo.

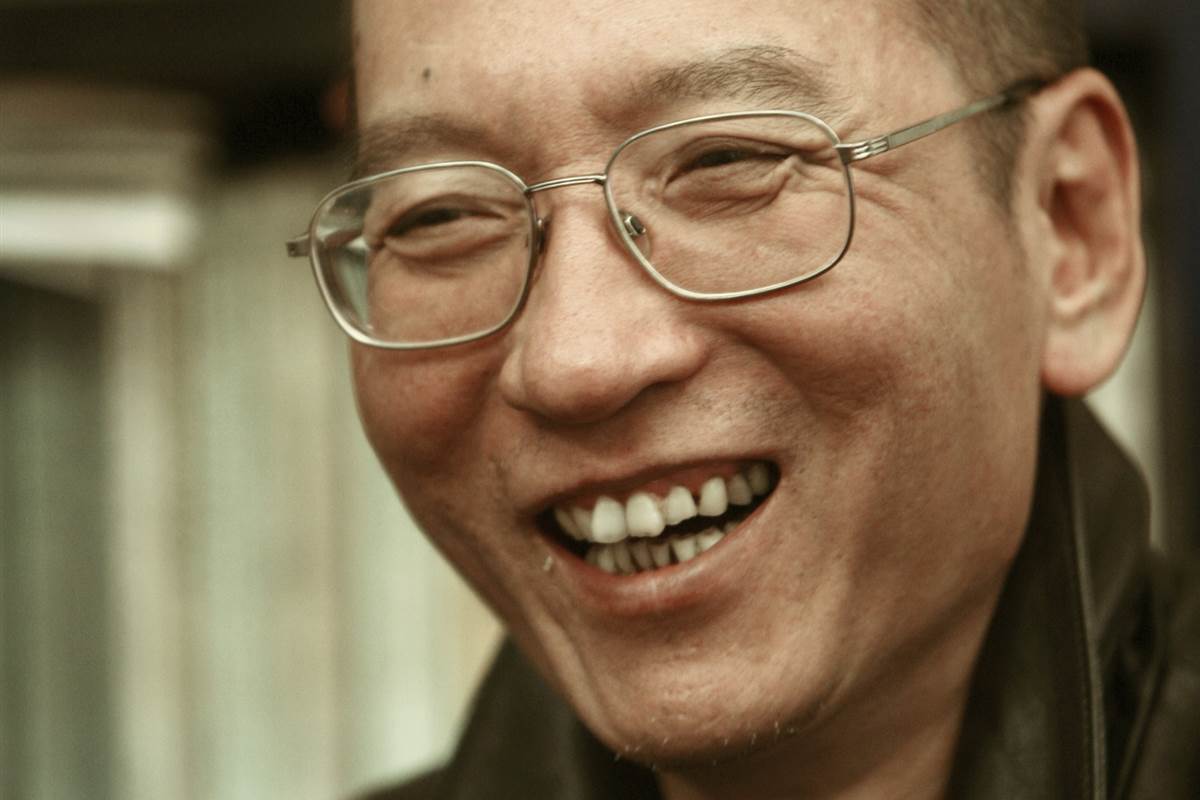

On Thursday, China allowed the revered dissident Liu Xiabao to die in custody at the age of 61, refusing to allow him to travel outside of China to seek treatment for liver cancer. Liu was the first Nobel peace prize winner to die in custody since the German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky, who died under surveillance in 1938 after spending years in Nazi concentration camps.

China, which has called Liu’s winning of the peace prize a “blasphemy,” typically called for the world to stay out of its “internal business” after Liu’s passing. The leader of the Norwegian Nobel committee on Thursday accused Beijing of bearing “a heavy responsibility” for Liu’s death, however. “This is ultimately a political murder,” Hu Ping, a fellow activist who had known Liu for decades told the Guardian.

True to form, China is attempting to maintain control over Liu in death as it did in life. Activist Hu Jia said authorities were pressuring Liu’s family to quickly cremate his body, only allowing relatives to hold “a simple farewell ceremony, under severe surveillance.” Ye Du, another activist and friend of Liu, said he had been warned by Chinese security services that he was not to travel. A “national ban” had been placed on activists hoping to attend Liu’s funeral, he added. The leader of the Norwegian Nobel Committee said on Friday that the Chinese consulate in Oslo had refused to receive her visa application for travel so she could attend.

Internet censors have also wiped out comments about Liu on Chinese social media, blocking search terms including Liu Xiaobo, LXB and RIP. The phrase “I have no enemies,” a statement Liu famously made in the courtroom, surrounded by those trying to destroy him, was ironically also banned.

Liu Xiabao became well-known in China in the 80’s as a combative, witty professor of literature whose lectures electrified students. He became famous when he took the side of the students in pro-democracy protests in Tianamen square, first as one of the prominent “four gentlemen” who launched a hunger strike in support of the students; then by helping to negotiate a peaceful exit from the square for remaining demonstrators amid China’s strong-arm response. China’s decision to jail Liu for 11 years over his support for the call for peaceful democratic reform was the inspiration behind the Norwegian Nobel committee honouring him with its peace prize in 2010, a move which angered China and made Liu an international celebrity dissident.

Liu was overseas when the pro-democracy movement erupted and went home despite the risks, echoes of Dietrich Bonhoeffer who returned home to Germany in 1940 to clandestinely fight the Nazis. Like Bonhoeffer, Liu paid a heavy and ultimately fatal price. For Liu, the immediate consequences were jail, an end to his career as a brilliant young literary professor, and the end of his first marriage, to Tao Li. His ability to see his son Liu Tao was also limited.

After 1989, many outspoken figures fled abroad or fell silent: “Others can stop. I can’t,” said Liu. It was in a labour camp in 1996 that he married the poet Liu Xia.

“A calm and steady mind can look at a steel gate and see a road to freedom,” Liu wrote of life as a prisoner. Liu insisted that love would overcome hate and progress would be made. Outside, however, the political repression only increased and China did not budge on Liu. Friends at home and abroad were enraged at the late diagnosis of liver cancer and the authorities’ refusal to let the couple go abroad or to show them clemency.

Liu Xia has been living under house arrest since 2010. Ms. Liu has found her isolation hard to take and has chronicled her suffering in poetry and art. In a rare interview in 2012, when reporters with The Associated Press managed to sneak past guards and enter her apartment in Beijing, she said, “Kafka could not have written anything more absurd.”

Repression in China has worsened in recent years as outside pressure has decreased and even once celebrity causes like Tibetan freedom have faded from public view. Sophie Richardson, the China director of Human Rights Watch, says that there is “progressively less interest in foreign governments in really fighting as hard as they ought to have for systemic change in China.”

Mr. Kamm of the Dui Hua Foundation, who works for the freedom of political prisoners in China, told the New York Times he would continue to present lists of prisoners to Chinese officials, however. Now he also plans to point out how the government’s treatment of Mr. Liu has hurt China’s image in the global community.

“I think they have taken an incredible hit on this,” Mr. Kamm said. “There are five prisoners on my list tonight that I will use this to try to get out of prison into their loved ones’ arms.”

Faced with death, Socrates famously argued that if the government was wise it would not execute him, but rather provide him a salary. Afraid of “mere” words and ideas, China continues to silence its gadflies.

Liu Xiaobo has already attained heroic stature in China and beyond, an academic who lost his life in order to speak for the good of the people in the face of the government. His example will continue to goad all of us into asking hard questions about the level of our own courage and steadfastness in the face of systemic injustice.

Matthew Gindin is a journalist, educator and meditation instructor located in Vancouver, BC. He is the Pacific Correspondent for the Canadian Jewish News, writes regularly for the Forward and the Jewish Independent and has been published in Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Religion Dispatches, Kveller, Situate Magazine, and elsewhere. He writes on Medium from time to time.