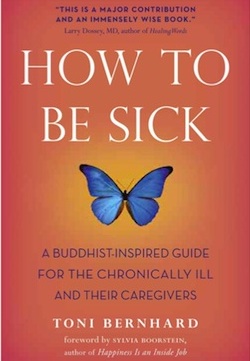

Toni Bernhard’s new book, How to Be Sick: A Buddhist-Inspired Guide for the Chronically Ill and Their Caregivers was recommended to me by one of my congregants who cares for a chronically ill loved one. She described Bernhard’s book as “How to be sick well” – how to achieve emotional and spiritual wellness even when one’s body remains sick.

Acclaimed Jewish-Buddhist teacher Sylvia Boorstein in her introduction to the book wrote, “This book is written for people who are ill and aren’t going to get better, and also for their caregivers, people who love them and suffer along with them in wishing that things were different. It speaks most specifically about physical illness. In the largest sense, though, I feel that this book is for all of us. Sooner or later, we are all going to not ‘get better.'”

Bernhard became ill in 2001 and has suffered from chronic illness ever since. She begins by telling the story of her illness and quickly moves to sharing how her Buddhist learning offered her a way of approaching her illness as a spiritual practice. She wanted to know “how to live a life of equanimity and joy despite my physical and energetic limitations.” This book offers her answers to that question.

…There is wisdom in accepting what is, instead of getting caught up in wishing that things were different.

She writes about the power of “just being” with what is: “Just “being” life as it is for me has meant ending my professional career years before I expected to, being house-bound and even bed-bound much of the time, feeling continually sick in the body, and not being able to socialize very often. [Drawing on Buddhist teaching,] I was able to use these facts that make up my life as a starting point. I began to bow down to these facts, to accept them, to be them. And then from there, I looked around to see what life had to offer. And I found a lot.”

I struggle a little bit with her language of “bowing down to” these facts. And yet I recognize that there is wisdom in accepting what is, instead of getting caught up in wishing that things were different. I know that in my own life I get into trouble when I get attached to my expectations of how something will be, and I feel more open to blessings when I can simply be with what is.

This is a book rooted in Buddhist terminology and thinking and Bernhard does a good job of explaining how these concepts relate to the life we all share. She writes about Buddhism’s four “sublime states” of lovingkindness; compassion; joy in the joy of others; and equanimity, a mind that is at peace in all circumstances – “Cultivating joy in the joy of others has been central in coming to terms with the life I can no longer lead. Without this, I’d be steeped in envy.”

Loving-kindness, compassion, and equanimity are all familiar ideas to me from my own tradition. But the idea of specifically cultivating joy in the joy of others was new to me. Bernhard explains that she has made a conscious effort to feel genuinely glad for people who got to do things she couldn’t do, and to consciously affirm joy in their good fortune. At first, she admits, that felt “fake” to her – but over time the fake practice became real, and now it is second nature.

Loving-kindness, compassion, and equanimity are all familiar ideas to me from my own tradition. But the idea of specifically cultivating joy in the joy of others was new to me. Bernhard explains that she has made a conscious effort to feel genuinely glad for people who got to do things she couldn’t do, and to consciously affirm joy in their good fortune. At first, she admits, that felt “fake” to her – but over time the fake practice became real, and now it is second nature.

The “fake it ’til you make it” approach is something I’ve experienced in Jewish practice, as well. As Rabbi Jeff Roth taught me many years ago, on mornings when I can’t access genuine gratitude as I pray the words of the modah ani, I can recite the words in the hope that gratitude will arise for me again. If I waited until I fully felt the meaning before I said the words, I might never pray at all. Sometimes saying the words with regularity is part of what trains my heart and soul to feel the gratitude and the awe which the words express.

And yet I recognize that for someone who is chronically ill, certainty and predictability are in short supply. On a given day, Bernhard may or may not feel up to getting out of bed, or seeing people, or leaving the house. Those are no longer the kinds of things on which she can count. But she writes poignantly about how, when she can let go of the desire for certainty, she can access a different kind of freedom. “Our tendency is, of course, to want our desires to be fulfilled. But if our happiness depends on that, we’ve set ourselves up for a life of suffering.”

Bernhard offers several valuable mental practices. One of my favorites is “dropping it.” First, she teaches, focus on something sad in the past (“there are treatments I regret having tried, and recalling them gives rise to stressful thoughts such as ‘Am I sicker today because of that potentially toxic antiviral I took for a year with no positive results'”) – and then just drop it. “Maybe you can drop it for only a microsecond, but just drop it and direct your attention to some current sensory input,” she urges, and feel the relief which ensues. And make this a regular practice. “With practice, you’ll find that at the command ‘drop it,’ the memory is gone and so is the suffering that accompanied it.”

I also really like her teaching about how to respond to one’s own frustrations with compassion. For instance, someone who is feeling sad and frustrated about missing a family gathering due to illness might say to themself, compassionately, “It’s so hard not to be able to join the family for dinner.” Like the teaching about thwarted desire, this one too makes me think of our son, because I often try to comfort him in this way: by letting him know that I hear him, and I understand what he’s feeling, and I empathize with where he’s at. But I hadn’t thought in terms of bringing that same kind of compassionate listening to the cries of one’s own heart.

This is a brave and necessary book, and I admire Bernhard tremendously for writing it. I hope that having read it will help me be a more compassionate and caring pastoral presence.

A version of this article was originally published on the author’s blog, The Velveteen Rabbi.

Since 2003, Rachel Barenblat has blogged as The Velveteen Rabbi. Ordained as a rabbi and spiritual director, she serves Congregation Beth Israel and is a founding builder at Bayit: Your Jewish Home. Her books of poetry include 70 faces: Torah poems (Phoenicia, 2011) and Texts to the Holy (Ben Yehuda, 2018).